The Syndicated Loan Market

by Tim Gramatovich, CFA.

Chief Investment Officer

Given our view of the current and future macro environment, we believe investors need to prioritize return “of” capital vs return “on” capital.

We believe the syndicated loan market is the best place to generate some offense while playing good defense.

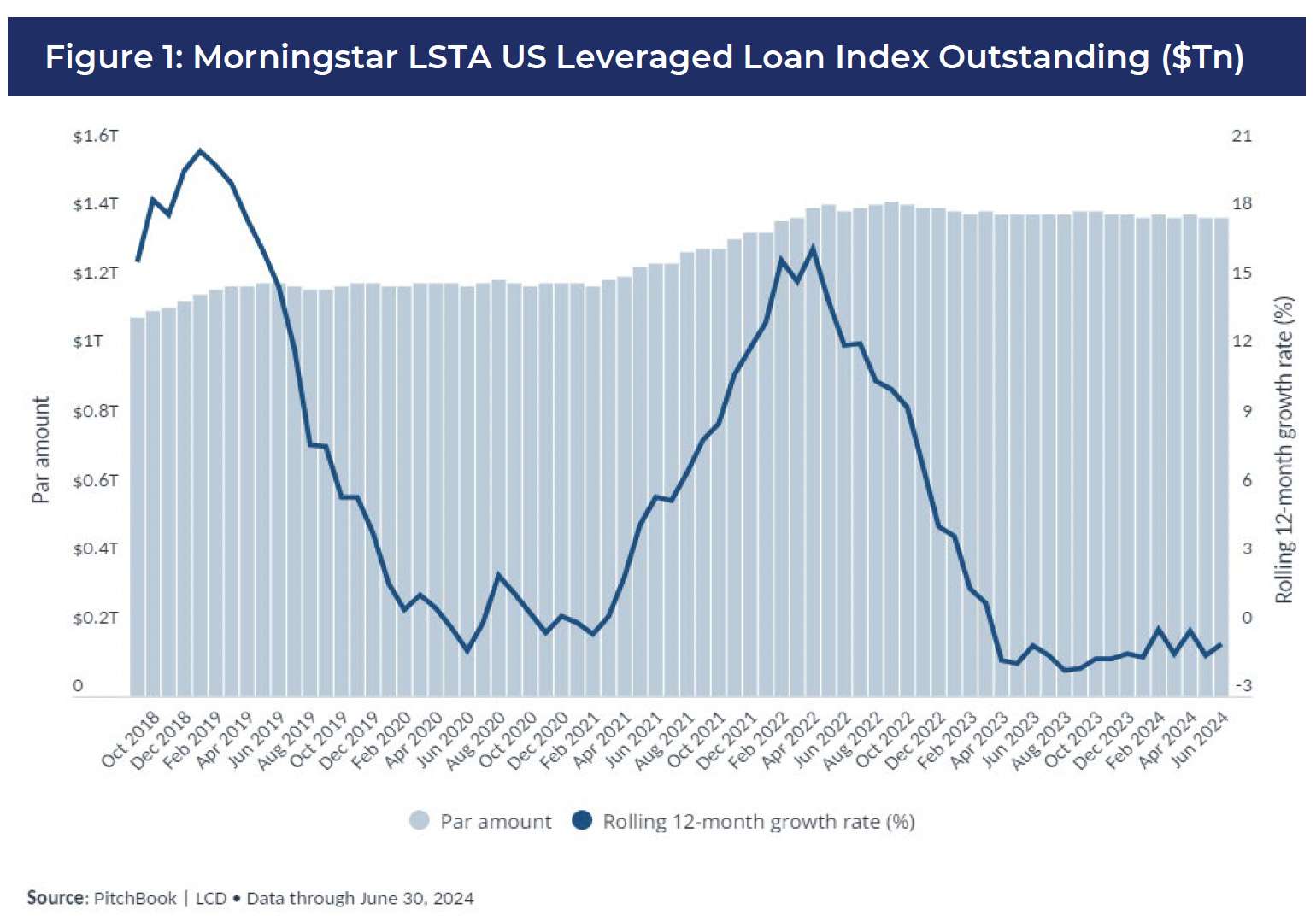

The institutional term loan market has become a major fixed income asset class and is now approaching $1.5 trillion. It is expected to continue to grow over the coming years, surpassing the high yield bond market.

When accounting for loans outside the leveraged loan index (refer to Figure 1 below) along with private credit and the “club deal” market, we estimate this investable loan universe is in excess of $3 trillion.

We first became involved in this loan market back in 2002 as we had a small opportunistic bucket for loans in our high yield bond structures. As credit investors, we have historically found value in smaller issues (i.e. sub-$600 million tranche size) because rating agency models consider size a very key input to their ratings. We will discuss this in more detail later in this document. Furthermore, this smaller market segment has almost fully migrated from high yield bonds to syndicated loans and “club deals” over the past decade. The biggest reason for this is that most large high yield ETFs and mutual funds have minimum size requirements forcing smaller issuers (i.e. typically below $600 million in issue size) into the loan market for term financing solutions.

Twenty years ago, this syndicated loan market was a rounding error, but its explosive growth stemmed primarily from regulatory changes generated by the Basel Accords, which were a series of three sequential banking regulation agreements set by the Basel Committee on Bank Supervision. Effectively, this legislation made it very costly (i.e. capital charges) for banks to lend to companies that are rated below BB. This led to banks originating and syndicating term loans to institutional investors versus directly lending to the companies. As this trend started to accelerate, the collateralized loan obligation (“CLO”) market exploded alongside as one of the primary buyers of these loans.

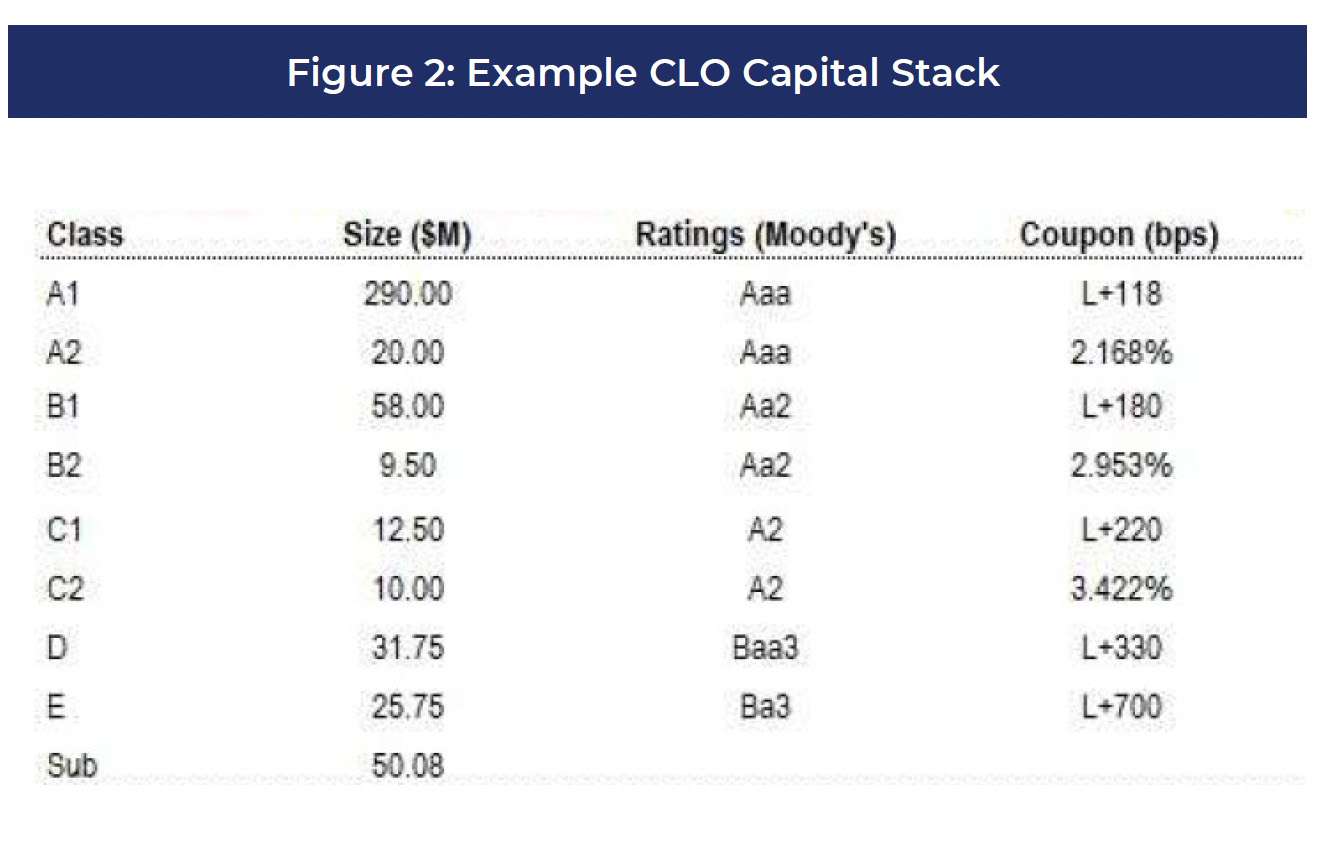

CLOs are a flavor of securitizations which involve packaging up a large amount of cash flowing assets (eg. corporate loans in this case) and applying leverage to enhance returns. This is no different than asset backed securities (“ABS”) involving credit card receivables, auto leases or mortgages (“MBS”). In a typical CLO, a manager buys a pool of these corporate loans (approx. 150-200 separate loans) and receives portfolio financing (i.e. leverage) against the pool of loans. Managers do not buy the entire corporate loan, but a small portion. CLOs are effectively synthetic banks—buying corporate loans with a levered balance sheet. In a bit of an ironic twist, the rated leverage is provided by banks and insurance companies. Standard broadly syndicated loan (“BSL”) CLOs are over 10:1 levered. Approximately 60% of this leverage is rated AAA as the senior class, meaning its interest gets paid before all other classes. This rating is key because both banks and insurance companies crave AAA assets as they get tremendous capital treatment there. Shockingly to most investors, the US has only two AAA companies—Microsoft and Johnson & Johnson. This makes CLOs and other securitizations critical to the financial system, hence their exponential growth. Below in Figure 2 is a typical capital stack shown for a $508 million CLO:

To get CLO tranches rated by the major rating agencies, CLOs have parameters that must be adhered to such as weighted average ratings factor (”WARF”), over-collateralization score (“OC”) and interest coverage (“IC”). But the core economics are not difficult to understand. You build a diversified portfolio of loans that generate interest income (assume 9.0%) and then use leverage with an assumed interest cost of 7.5%. If you apply leverage of 9x, the effective gross yield before fees would be 13.5% (1.5% x 9). Most individual investors have limited knowledge of the CLO market. The CLO business is dominated by the largest private equity firms attempting to maximize leverage and assets under management such as Apollo, Carlyle and GSO-Blackstone. Other prominent players include Ares, Blackrock, Prudential, Credit Suisse, and specialists such as Anchorage, Brigade, CIFC and Golub.

While CLOs are a big buyer in the institutional loan market, they are most dominant in primary or new issues. Banks, insurance companies and investment funds all play a major role as investors and market makers which has created a liquid secondary trading market for loans. We have historically sourced almost all of our loans from the secondary market, and our experience in trading off-the-run credit provides us with a significant advantage over our competitors. This advantage allows us to add value through execution and sourcing of unique loan investments.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

All thoughtful investors realize that leverage is a double-edged sword. If you are leveraging good assets, it is an excellent strategy. If you are leveraging bad assets, you have the financial crisis of 2008. Fortunately, both corporate loans and CLO structures have been tested in 2 major downturns over the past 15 years: The financial crisis of 2008, and recently the Covid pandemic. The underlying loans and the structures performed very well.

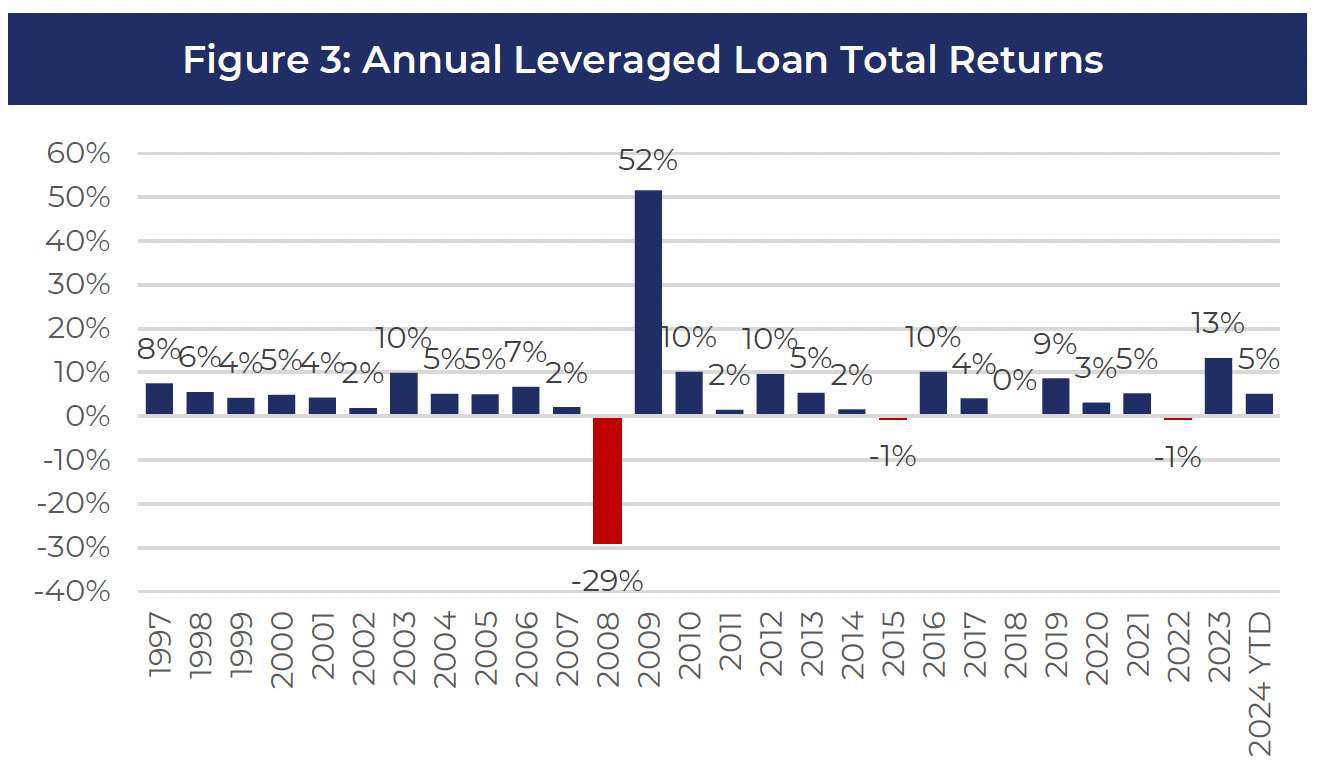

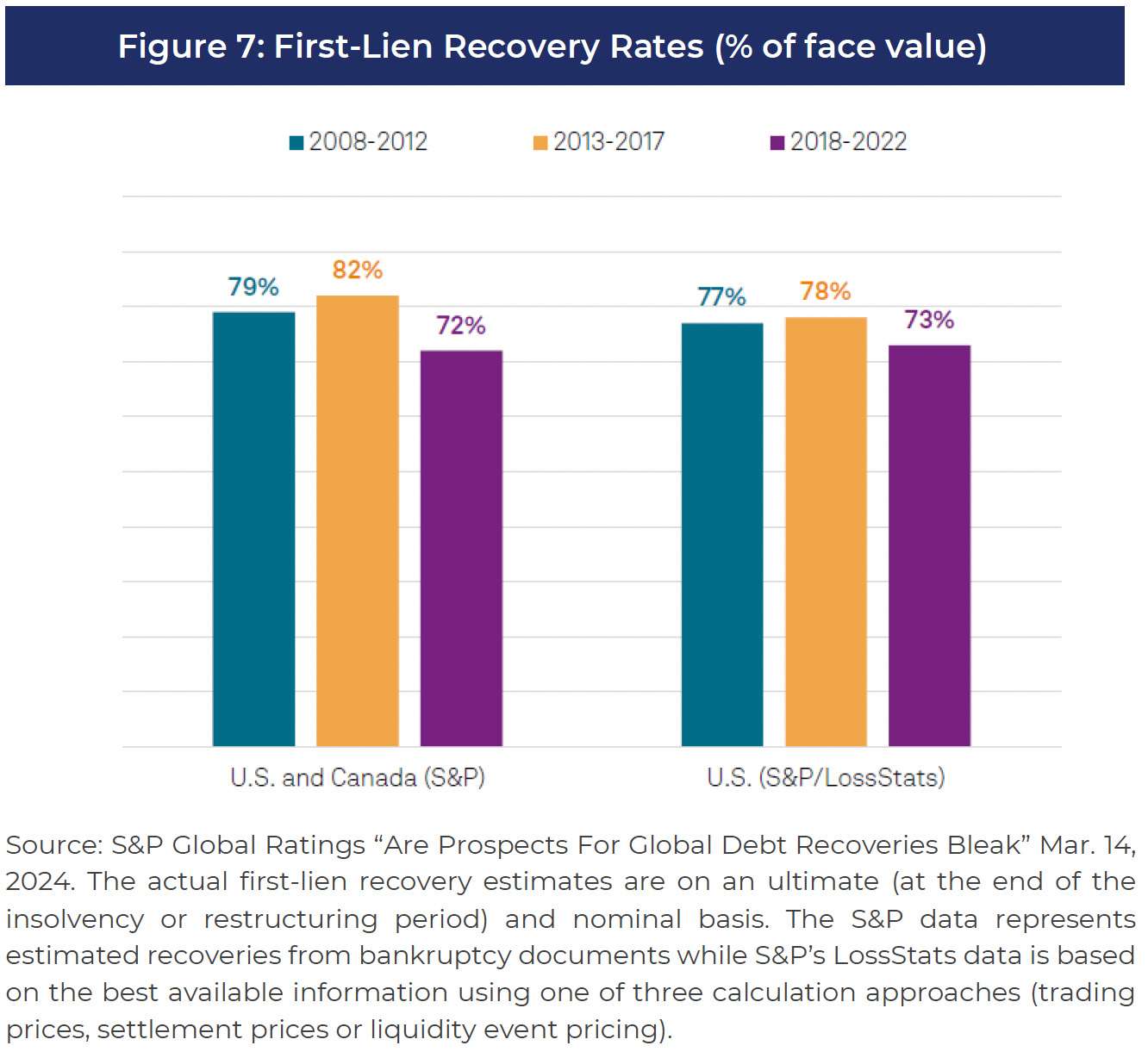

Loans have many attractive attributes including a true 1st lien secured loan sits on the top of the capital stack with a 1st lien on all of the assets of a company. In a default, loans have historically recovered above 70% since 2008. Institutional loans are floating rate and carry a low-price sensitivity to interest rate changes. Additionally, loans historically have low volatility compared to other asset classes and have shown only a single negative year in the past 3 decades, (the financial crisis of 2008). The market fully rebounded in 2009 (refer to Figure 3 below).

An additional advantage for loan investors is detailed financial reporting beyond what most public market investors receive such as budgets and monthly reporting. Institutional loan investors have truly become the banks for a large part of the corporate sector and have greater liquidity in the secondary market.

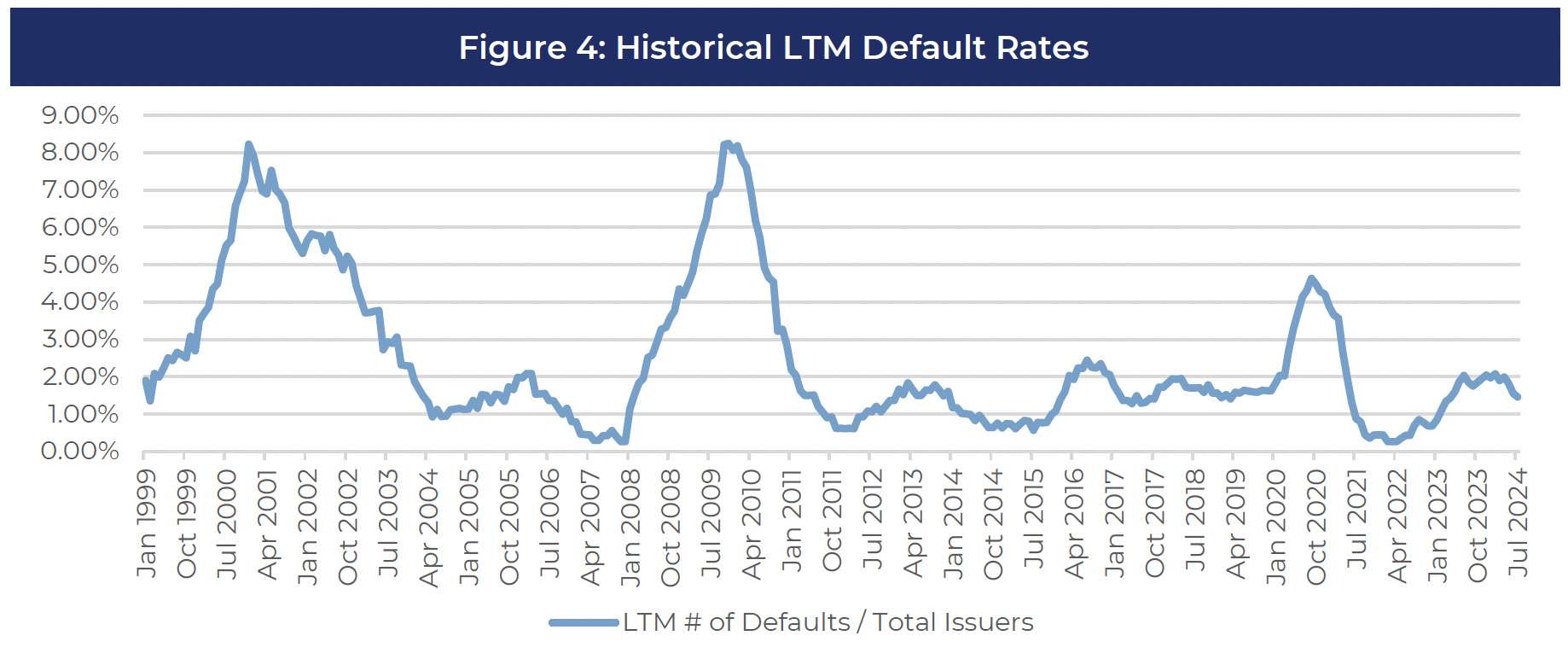

On the risk side of the equation, default rates have been relatively benign over the past 25 years (refer to Figure 4 below). The spike in 2008 skews the average number to around 2.5%, however, without this spike 2% is more representative.

In our view, legitimate 1st lien loans should recover no less than 65% in a default scenario, which would make your annual loss rate around 0.7% (2% x 0.35). If the expected current yield of a loan portfolio was 9%, this “risk-adjusted” return would be 8.3% in loans with true first lien collateral.

We expect the default rate for higher levered capital structures to increase over the next year but remain below the market average. Defaults typically arise from falling cash flows which in turn triggers a maintenance covenant from deteriorating credit metrics. Interest coverage ratios are supported today by strong cash flows and have been surprisingly resilient in the face of significant rate increases. Spread compression has helped in a big way allowing an additional wave of refinancings at very tight spreads. The second key part of the systemic default story arises from a lack of liquidity. This is something that is just nowhere to be found even in a relatively benign economic environment. Through CLO formation and massive fund raising from private credit, money continues to flow unabated into the leveraged finance space. While loan leverage is historically elevated, balance sheets and liquidity are still excellent even if we are headed into a recessionary environment. We always assume we are in a recession heading into something worse as we want to ensure our loans can both pay and refinance in any macroenvironment.

This is the good.

Let’s turn our attention to the bad which is not all that bad from an investor’s perspective but presents challenges to us as managers. While loans trade with identifiers (i.e. similar to a CUSIP for bonds), they are not in fact securities which makes them more difficult to settle. In the early days of trading, it could often take months to actually settle a trade. Today the Loan Syndications and Trading Association (“LSTA”) has standardized documentation and settlement is now measured in days not months. The lack of call protection is another potential issue to us as investors. In high yield bonds, we typically get 2-3 years of hard call protection where the company cannot refinance, and then a hefty call or refinancing premium beginning in year 3 or 4. In loans, call protection is almost non-existent and is generally 6 months to 1 year of “soft” protection meaning no repricing of the loan until after that period. There is almost never a call premium involved.

That is the bad.

Now let’s turn our attention to the ugly because there is always an ugly. If you can’t identify the ugly upfront, it will pop up like a jack-in-the-box at some point down the road. In this case, the “ugly” is very aggressive underwriting behavior as the cycle has moved into the later innings. Discipline evaporates when markets get popular and underwriting requires in-depth fundamental analysis. Documentation is the first part of the challenge. Loan covenants are a part of the credit agreement between the borrower and lender stipulating terms and conditions of the loan. Over the years, these documents have become far more borrower friendly which we always consider a detriment. Poor documentation will become more evident in a down cycle. Moreover, and important to us, starting in about 2018 we began to see companies getting both investor and rating agency approval for very aggressive addbacks to boost their EBITDA.

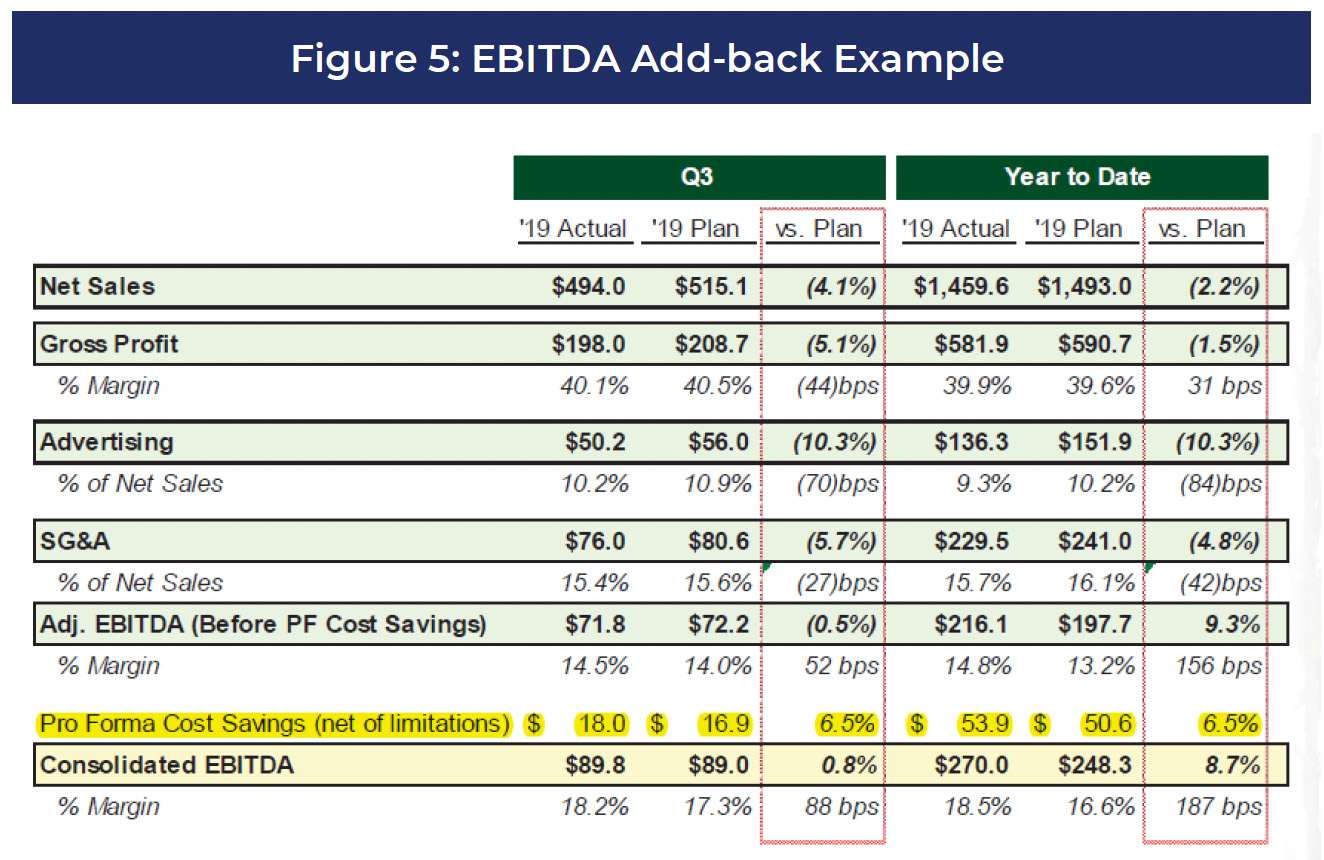

This became known as “pro-forma further adjusted EBITDA.” Companies are given credit for synergies and expense reductions that might happen in the future. Obviously, this can create fictional metrics and make things appear far better than reality. Below in Figure 5 is a real example we came across on a transaction all the way back in 2019:

So adjusted EBITDA of $216 million was magically increased to $270 million with $54 million of “future costs savings” addbacks. In our analysis even the $216 million used certain adjustments we would not agree with. We believe the loan market today includes a significant amount of these fictional adjustments which can provide an inaccurate leverage profile. Leverage is the most important measure of risk to us, and we believe an active portfolio management process is critical in avoiding these fictional adjustments.

That was the ugly.

Turning the Frog into a Prince

OK so now that we have identified the warts, how do we mitigate these challenges? In a word — work. We are uniquely qualified to operate in this environment because we have been high yield bond investors for the last three decades. High yield has historically been unsecured debt meaning it sits below the bank debt but above the equity. We have always viewed it as equity with a coupon because if you get it wrong and the bond defaults, you get very little recovery. So while loan documentation has deteriorated, to us it remains a source of comfort—we actually have security and collateral which would point to a higher recovery value in a default scenario. When you have operated without a safety net, this improves your outcomes. But the moral of the story remains the same— don’t get it wrong.

The objective of all investors is to generate excellent returns while limiting and managing risk. In investor parlance — “alpha.” For us this begins with what we call a “size arbitrage”. Companies that have revenue lines below $1 billion suffer a lower rating (i.e. CCC) for a chunk of their credit score.

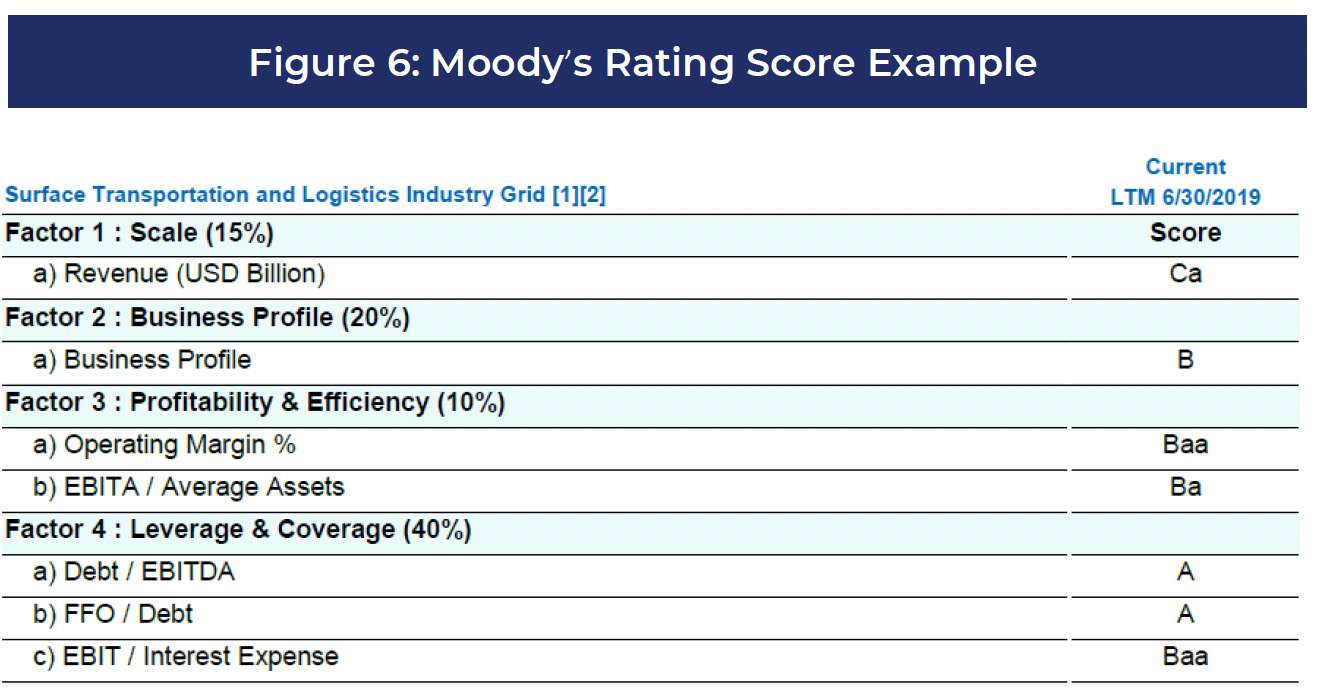

A company with $900 million of revenue could be rated significantly lower than a company whose revenue is over $1.0 billion, even though it may have better credit fundamentals. These lower ratings can often provide us higher yields with below average leverage. We provide a tangible example of size ratings skew from a Moody’s preliminary rating grid in Figure 6 below.

This company had $500 million in sales which generated a “Ca” rating for a chunk of its score. The “Business Profile” section is also size related, and this company received a “B” rating here. For fundamental credit investors Factors 3 and 4 are priorities and these received excellent ratings. So, a combined score can be far lower than what fundamentals would suggest providing us the “size arbitrage.”

Since we are not a fan of jargon we define “alpha” succinctly as yield per turn of leverage. How much yield are we being compensated with for the risk we are taking? Leverage in this case is defined as the company’s Net Debt/EBITDA. We use a leverage metric as we believe this is the key risk factor in determining both future defaults and recoveries. Our goal is to “fully underwrite” a 60+ name loan portfolio that has overall company leverage of less than 3.5x on a Net Debt/EBITDA basis. This leverage number is not random but is a product of my experience in bankruptcy court in the 1990s. Historically bankruptcy judges did not want companies exiting bankruptcy with a high leverage number as they did not want them to return. While this number is considered incredibly antiquated (i.e. way too low) by most market participants today, we feel it adds a layer of protection to our portfolio. Our typical “exit” primarily comes in the form of a refinancing. If leverage is manageable, the odds of the company being able to access debt capital markets for a refinancing is very high. In addition to manageable leverage, we want our companies to have excellent liquidity in the form of excess cash and/or revolver availability, and most importantly to be able to generate healthy free cash flows which we define as cash flow from operations less capital expenditures. EBITDA is not cash flow but a convenient and helpful valuation metric.

To be clear, we are not originating loans but screening for names in the secondary market, fundamentally analyzing each name and purchasing a portion of the loan with an objective of eliminating defaults. With this active management process, we expect to have a lower portfolio default rate than the market average which has historically been around 2%. Because the portfolios are going to be first lien debt, even in an event of default we would still expect strong recoveries (refer to Figure 7). The ugly behavior has led to recovery rates decreasing, but these are still at a very healthy level.

The final question relates to where the loan asset class fits into an investor’s portfolio. I would make an argument that a carefully selected portfolio of low levered, true 1st lien term loans that could earn yields of 400 – 500 bps above the risk-free rate should be a major component of a core fixed income portfolio today.